A weird thing has been happening to my voice recently.

It quits.

It just cuts out mid-speech. I go hoarse, and I have to clear my throat several times to get it going again.

I’ve had enough therapy to draw my own somatic conclusions. For the past year, I’ve become used to fighting the urge to scream and vomit several times a day, and I know that I’m far from the only person who is holding an ever-filling well of pain inside themselves that is so close to overflowing that it ends up choking us.

So, a question:

What are you doing with your rage?

If you are not feeling rage—if the nightmare that has incessantly unfolded over the past year has not left you feeling furious, and helpless, and radicalized, and bereft, every single day—then this post probably won’t resonate.

To go back to the question, addressed only to those who feel incapacitated by the daily, gaping wound left in place of their faith in humanity and society:

Where are you putting these feelings?

Mine have not gone into my writing, at least nothing that you can read. These days, I feel like a sham when introducing myself as a writer. Someone asked me the other day how long this had been going on and I replied, “Oh, since around October 7th last year?” The reason I haven’t been publishing is that in lieu of any kind of lucid narrative is mostly just incoherent, internalized screaming. I wish I could scream out loud, my god, the idea itself is a relief. But I don’t, and my furious journaling, discarded drafts, and ephemeral social media posts are the closest I’ve come to any sort of articulated expression.

That’s because sharing how I feel—how I feel?!—seems so breathtakingly narcissistic. In the company of my friends from the Middle East, I try to focus more on listening; I’ve discovered there is so much I don’t know and there is a real risk that voicing my own horror would seem both selfish and ignorant. As a conscious and woke society, we’re taught that there is nothing less helpful, and more cringe, than wailing and hand-wringing.

I’ve had many conversations with friends who are far better informed, and more personally impacted, for whose perspective and generosity I’m eternally grateful. Through speaking with them, I’ve also perceived an impatience—understandably—for people who are only recently “getting it”. My friends are people who have been living with the reality of what the rest of us are seeing now for generations; our revelations are not news to them. There is a sense of annoyance, of “so nice of you to finally join us,” that makes me feel ashamed. I believe that the abashment we feel is appropriate, but also that we should always welcome the correct response, however late it arrives. We are all products of our systems, and those of us who have been systemically unaware—even ignorant—are finally awakening to truths our societies have intentionally kept us blind to.

So many of us are on the other side of our screens, insulated by the safety and privilege of being from the imperialist countries that are funding, supporting, and enacting a campaign of genocide and ethnic cleansing. We are not affected, directly; but there must be something to be said for the second-hand trauma of bearing witness. This, too, is a historical perspective; and when we speak of the history of this time years from now, this lens—that of the horrified witness—is one through which it will be told. But right now, my impulse to scream is getting so overwhelming and debilitating that I need to do into the void (the internet).

One reason for needing to express myself is that I am paralysed from being able to express anything at all, because everything else feels so meaningless and banal. I’m grateful these days to the extent that I appreciate existentially mundane inconveniences—what kind of a complaint is this? Who am I, to feel wronged? How lucky am I, in the scheme of things? As true as these sentiments are, they result in the invalidation of the experiences that comprise my life; experiences that I committed, five years ago, to expressing as a writer. It took me a long time to call myself a writer, and longer still to call myself an artist. This year, I started working on a book called “Make Bad Art”, its purpose specifically intended to encourage artists to overcome the fear of judgement—primarily their own. It’s not a coincidence that progress on this book, too, has stalled; how can I tell others to do what I cannot do for myself?

I have felt less afraid of saying how I feel for how it might be received by others. One of the great qualities I’ve been gifted by autism is a very clinical sense of justice. I know many people are afraid of losing jobs, friends, and social standing—for me, value alignment has always been the most important metric for all of the above. I cleared my freedom to express my position with my clients last October—luckily, my immediate teams are similarly aligned and, as a freelancer, so far I am afforded relative carte blanche over my views without representing an organisation. I have, however, lost friends—in particular, one of my closest and oldest friends. This has been a great bereavement, albeit moderated by my disappointment in her unwillingness to communicate and engage in conversation about our differences. A moral crossroad like the one we’re at shows us that perhaps we never really knew the people we love most, which I’m sure is a feeling we share.

Friends who have chosen not to take a view for the sake of comfort have also disappointed me. I’ve been surprised by the number of people in my community over the past year who have either chosen to say nothing or to stay uninformed, toeing a politically-safe party line. I’ve been even more cognisant of this since the invasion of Lebanon; my community in Berlin is largely Lebanese, and I know from talking to friends that people—some of whom have visited friends in Lebanon and availed of their hospitality—have suddenly gone mute. A friend told me that he counted on less than one hand how many people had reached out to him in the weeks since the first bombing. It is one thing to not have the words, it is another not to try. Does awkwardness really supersede compassion? That is, assuming it is awkwardness.

Dr Maya Angelou said, “We are only as blind as we want to be.” This feels especially acute in Germany, with its legacy of holocaust guilt and an algorithmic value system that seems programmed by specific variables; it’s a society that seems to understand that a certain type of never-to-be-repeated-to-a-specific-people genocide is bad, but not another. A Lebanese politician friend told me that Germany is the worst of the Western countries funding the genocide because “for 80 years they’ve maintained a pretence that they learned something, but in the same situation they’re repeating the same behaviour all over again.” They might argue that it’s not the same, because there is a different variable.

Still, the suggestion that it speaks to a certain cultural propensity is chilling. In June, I heard Dr Gabor Maté—a holocaust survivor—address an audience in Berlin. He stated upfront that he was not there to change anybody’s minds because if they wanted to understand the history of Gaza’s occupation, they already would; it was not as if the information—80 years’ worth, let alone the past year—was not available, so to claim otherwise was a wilful act of ignorance he had no interest in engaging. While being quick to call out antisemitism, the softly-spoken Dr Maté was emphatic and unsympathetic about Germany’s urgent need to deal with its historic guilt: “You are so blinded by your guilt that you cannot see the victims of your victims.”

On the whole, my entire lens has changed. I have always questioned everything—another spectrum-given gift—and lately, I have become deeply suspicious of the Western point of view. For example, over the summer I fell into a rabbit hole of manifestation and the law of attraction; the paradox was that while I could see, on a personal level, that this shit works, I couldn't get past what a profoundly privileged practice it is. How in the hell are you going to tell someone in Gaza who lost 10 members of their family in one day, mothers who see their children thrown into pits alive and covered by dirt, and people whose remains are reduced to body parts in plastic bags, that their reality is the one they create? I at once practised and was disgusted by magical thinking, a conflict that compelled me to find purpose in my privileged ability to influence a reality that reflected my intentions. I began recording a series of content that asked us to question our safety not as a right but as an assignment—not to live our best lives for ourselves, but to recognise the potential for impact that gives us. I’ve always believed that our privilege gives us power, and an obligation to pay it forward.

But I may be asking too much of people, because I’m asking us to let pain in. I’ve been thinking lately about how, as a society, we’re not equipped to feel big, hard feelings including—especially—grief and anger.

Not only are we not given the tools to deal with our discomfort, we’re actively given more and more tools to distract ourselves from it. When we don’t like what we see and how it makes us feel, we can just look at something else. In personal relationships, this can lead to abandonment and invalidation; on a systemic level, apathy and disassociation. It’s too easy to avoid feeling uncomfortable and the upshot is, not only are we avoiding each other, but we’re also avoiding ourselves. I can understand—the enormity of it is overwhelming. But surely, we want to do better? To be better? It’s not that our society isn’t obsessed with self-improvement, so why are we applying our enthusiasm for betterment so selectively?

My theory is that our Western culture of personal growth, mental health, spirituality, and wellness has a serious problem: it is focused on the self. How to make ourselves better. As I asked in one of my videos: When we are better, who is better off? I see this especially with men who are focused on peak fitness: When your grueling training prepares you for superhuman feats, who wins? Who are you trying to beat? If what drives us to be better is not the question, “For whom?” and if the answer is “For myself”, we are just taking up space.

The past year has shown me with great clarity that our society is deeply devoid of a service mentality. There is a difference between being in servitude of others and serving another. In a recent podcast with my friend Anthea Bell, I discussed being raised in Eastern and Southern cultures that are community-oriented. In a society with a collectivist mindset, we think about others; we think about who we are in relation to everyone else. We are aware that we are sharing space, and less that others are encroaching upon ours. That’s evident in our homes and our communities; we’re hospitable peoples, concerned with how others feel not only in our company, but even when we’re not there. We think beyond ourselves, about the next person.

I’ve been paying close attention to this, from smaller to systemic degrees. It’s always irked me that in cafe restrooms, where toilet paper is abundantly stacked, people will leave an empty roll in the holder for the next person. Someone has to change it—why not you? I’ve also noticed that in the shower rooms of incredibly privileged shared spaces, people would leave their wet towels all over the floor in the private cubicles instead of in the designated bins—again, for the next person to pick up. These are minor examples indicative of a wider, pervasive mentality of thinking only about oneself, not of the next person.

Then over the summer, I had a more eye-opening experience. In Mauerpark, a large public park that is crowded on summer days, I saw a small child fall off his bike and hurt himself. He began to cry, loudly—not for attention, but because he was hurt and he was scared. I watched and waited for his designated adult to show up, but no one came. It’s a Western thing, I feel, to not intervene in the business of other people’s children—but it is absolutely not my nature to not feel deeply distressed by a crying child, and I watched dozens of people, groups of adults, walk right past this hurting child. I finally went over to help him find his parents, and myself and another person were able to locate someone who could take him to his parents.

This was a profound awakening for me. If people here don’t care about a child in pain in front of them, how can we expect them to care about a child in pain on the other side of the world?

I don’t know what to do about this except invest every ounce of my being into getting people to care more about the people around them. To ask people to think about themselves in relation to others, leveraging the gifts that I have—relationships, connection, writing—to reach the humanity and hearts of people in my community. I know I can’t make a difference on a macro level in my lifetime—I can’t change politics and leadership nor influence Western imperialist agendas—but if my life has any meaning, it will be to encourage people to feel their feelings and metabolise the same helplessness I feel into a charge that will empower the next person.

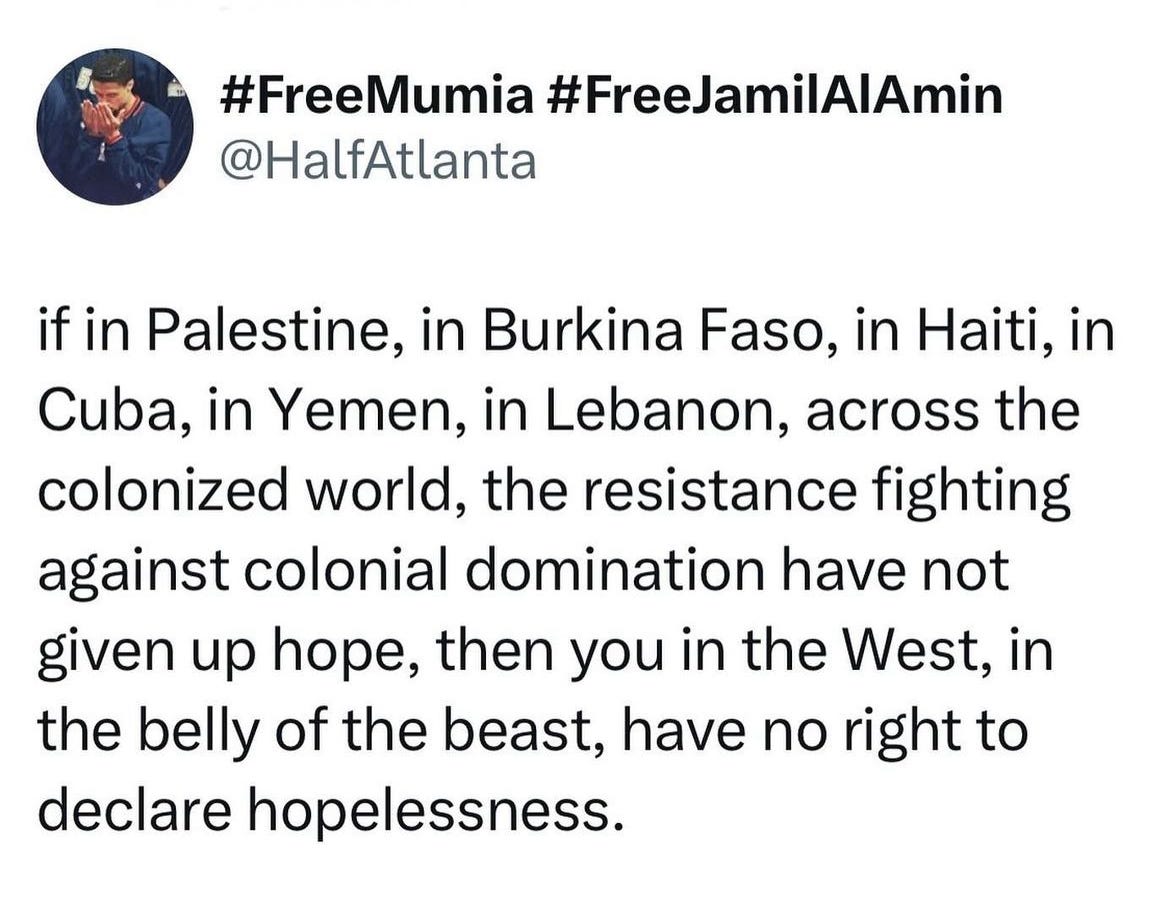

I saw this post the other day:

This is the first crisis of our time, at this scale, that has been live-streamed to our devices in real-time and called on us to stand for something. Malcolm X said, “A man who stands for nothing will fall for anything.” I’m seeing many people who seem to stand for nothing, and the way we engage with social media plays an enormous role. I’ve realised that my disbelief about how little other people are engaging says a lot about what they’re choosing to see—and if they don’t feel how I feel, it might be because they’re not seeing what I’m seeing. (The alternative, of course, is that they actually don’t care.) That is a conscious choice for a lot of people, and our algorithms reflect where we’ve decided we want to live.

Social media has become my source for real-time news. Though there is always something to be said for misinformation and a discerning consumption of user-generated content, it is a preferable alternative to the egregiously biased, agenda-driven Western media that, frankly, has been a fucking disgrace. I heard a commentator call TIME, among other outlets, “an imperialist mouthpiece,” and he is right. But it doesn’t change the fact that the saturation of social media is psychologically debilitating—I’m so overwhelmed by content that I want to take a break from social media but I just don’t trust other news sources. So I just keep doomscrolling (which has never been truer than it is now) without a healthy outlet for releasing the pain and anxiety that keeps building.

What I need most days is a hug—wholesome physical contact—which has made being single and living alone harder than ever. Aside from the fact that this is a fundamental human need, I think often of advice given to caregivers of autistic people: in the middle of a meltdown—a neurological response to overstimulation—one of the most helpful things you can do is to embrace the person and hold them tight until they relax. Decompressing my nervous system could be this simple, but that release is only possible with the aid of another. I’ve thought many times of calling someone who could probably use a hug too and asking if we could just hold each other, but as a single woman, that’s both complicated and weird for reasons I probably don’t have to explain.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how James Baldwin said, “I can’t afford despair. I can’t tell my nephew, my niece. You can’t tell the children there’s no hope.” As I spend a couple of weeks now with my niece and nephew, I do despair. We’re seeing the irrefutable truth of what humanity is and it seems to be people who harm (and are enabled to do so), people who scream into the void, and people who look the other way. I’m not shocked by much—people’s personal preferences and predilections, however disparate from mine, don’t trouble me—but the only thing that shocks and distresses me to my core is the human capacity for cruelty. On such a scale as we are seeing now, it seems impossible not to despair. And then I see reminders like this:

Accepting our reality—one where some lives have less value than others, where there is a double-standard that always, always, justifies the killing of Black and brown people—is not an option to me. If I can’t hope, I’ll at least refuse. At the very least, I’ll implore us to commit to seeing one another, to living outside of ourselves. Where we live, we talk a good game about mental health and spirituality but never about spiritual health—that is what we are together, as one entity. We are not separate. How many people think about how who they are impacts everyone around them? How spiritual are we when we believe ourselves to be insular?

In the absence of humanity, I’ve leaned more deeply into my faith. I’ve been talking to God, a lot—that is, the God I feel in myself and the God I can see in others. That is what God is, to me: it’s us. It’s each other. I really believe that anyone who denies that and still calls themselves religious or spiritual is worshipping something else entirely. We have only to look at the heinous war crimes being committed on behalf of a religion to see what William Shakespeare said in The Tempest: “Hell is empty and all the devils are here.” We are all we have, and it is our job here to be the best we can be for one another. The word namaste has been co-opted by Western wellness and I wonder how often people, at the end of a yoga class, think of what it means—the divine in me sees the divine in you—and put it into practice.

So be devastated, be furious. It is not only entirely appropriate, but necessary. And talk about it, if nothing else than for accountability’s sake. When we are asked about it decades from now, what will we say? Who will we say that we were? We need to think about this now, because I believe we will see a near future where IDF soldiers who committed unspeakable atrocities, and took pleasure in doing so, will be walking, living, holidaying, and partying amongst us, never held to account. Will we pretend nothing ever happened? Can we acknowledge that what they did is an extension of who we are as a society, and that who we are today is a measure of our own culpability?

I noticed a while back that the people who are advocating now are the same people who have done so from the beginning. I’ve seen little to no ground broken by those who have always been quiet. It’s not surprising that the people who advocate the loudest are from the same communities who are being decimated. If we have learned anything from social movements of the past decade, surely it’s that the burden of advocacy must not fall on the same people who are being marginalised.

As a society, we always end up asking the people who need support to be the ones who educate us—and now, many of us aren’t even listening to them. I want to be clear that my call for advocacy exempts the communities who are traumatised by seeing their people and homes destroyed, who are calling out for support or even acknowledgement from the rest of the world. That is why allyship matters.

“Allyship” was a buzzword when it pertained to the experiences of marginalised people in our immediate communities with whom we shared friends, workplaces, and social spaces; lately, it’s gone awfully quiet, as if it’s a choice that can be discarded. This makes me think that the people who took up allyship when it was relevant to them did so not out of a duty to be genuinely supportive, but because they didn’t want to look bad. I know that people get sick of my incessant posting about genocide, but I’ll take this over the flagrant use of social media that acknowledges nothing and platforms only ourselves.

This is far from all I have to say about this—I haven’t even got into the US election and Sudan, among other current crises—but the post has to end somewhere. I’ll end with a disclaimer: In the past, when I’ve shared very honest posts, I’ve had kind readers reach out to sympathise. Please refrain from doing so this time and instead, reflect on your own responses to what we’re witnessing now. If what I’ve shared makes you feel supported, I’m glad; if you’ve been holding back from expressing yourself openly, I hope this post gives you the encouragement to do so. If it makes you feel uncomfortable or even angry, I ask you to hold your discomfort for yourself and interrogate that response.

Thanks for reading this enormous exhale of a letter,